Selections in Cementation

Avoiding Crestal Bone Loss

The final implant restoration is something that every dentist must consider carefully for the benefit of the patient and the overall long term success rate of the treatment.

The success or failure of a root form implant often hinges upon the final restoration itself and how it is actually secured to the implant.1 Is it cemented or screw-retained? Which is possible? Which looks better cosmetically? What are the long term ramifications? These are all questions that the restoring practitioner much answer and comply with. Ultimately, the preservation of crestal bone around any implant is the paramount goal of every implant dentist and the method used to secure the crown can create significant issues contributing to crestal bone loss and even implant failures.2, 3, 4, 5

Because both screw-retained and cemented restorations falling into the fixed category, it is up to the clinician to decide which restoration is better for the patient’s individual situation. Because of this, it is imperative that the restoring dentist be involved in all aspects of decision making, from initial treatment planning to implant selection to final restoration and even recall care.6 Quite often, the general dentist is required to work within the parameters created by the implant surgeon or specialist.

By not considering the initial implant design and defaulting initial implant decisions to that of the surgeon, the restoring dentist severely limits their ability to choose an implant design that may be more advantageous to the overall treatment plan.

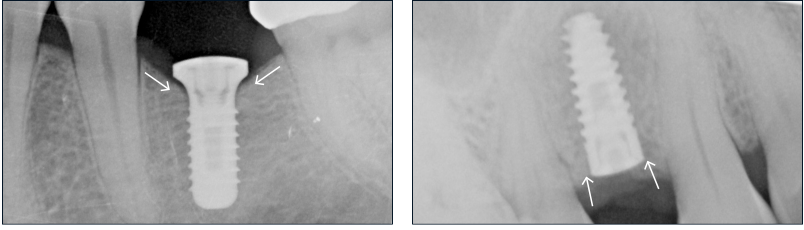

Figs. 1, 2 – Teeth 29 and 19, restored with screw retained crowns. Access holes filled with composite resin leading to non-ideal cosmetic results.

Some of the potential issues are the type of implant used (bone level vs. tissue level), implant placement depth, the esthetic location of margins, angulations, and other restorative hurdles. All of these specific points can have dramatic effects on the final restoration and more importantly, the long term success of the case overall.

Cemented fixed implant restorations have long been proven successful for replacing missing teeth in a bio-mimetic fashion.7 Cemented restorations can also lead to a final solution with superior esthetic results when compared to those of screw retained restorations, especially in the posterior areas (Figs. 1,2).

Because they closely duplicate standard crown and bridge procedures common to every practicing dentist, cemented implant restorations offer a phenomenal long term answer to missing teeth (Figs. 3,4).

By eliminating cumbersome implant restoration processes and getting the dentist back to familiar territories, cemented restorations offer confidence to dentists wanting a simplified approach to restoring implants.

Figs. 3, 4 – Teeth 8 and 12 restored with cement retained crowns leading to excellent final cosmetic and functional results.

Even though it has been proven that cemented restorations can deliver wonderful long term results, significant cementation issues can occur that can lead to catastrophic bone loss and implant failures.8

Because this specific step is so crucial to the overall success of the restoration, the cementation process must be planned and executed properly. The author addresses some of the potential issues related to cemented restorations and solutions to these associated problems.

1. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

By planning early and often, many problems associated with cementation can be avoided and possibly nullified entirely. According to the Journal of The Canadian Dental Association, peri-implantitis is defined as “ Infectious disease that causes an inflammatory process in the soft and hard tissues surrounding an osseointegrated implant, leading to the loss of supporting bone.” Unfortunately, minute areas of cement acting as calculus upon the axial surfaces of implants are wonderful vehicles for bacteria to adhere to, causing inflammation to persist and bone loss to occur. Obviously, bone loss is highly undesirable, but it must also be considered that bone loss leads to gingival inflammation and ultimately, gingival recession.9 Continuous healthy crestal bone and gingival tissue is critical to the long term success of any implant or implant procedure.

Once an implant is placed, the prevention of peri-implantitis is of the utmost importance and all restorative decisions are focused on the ongoing preservation of surrounding hard and soft tissue bone structures.

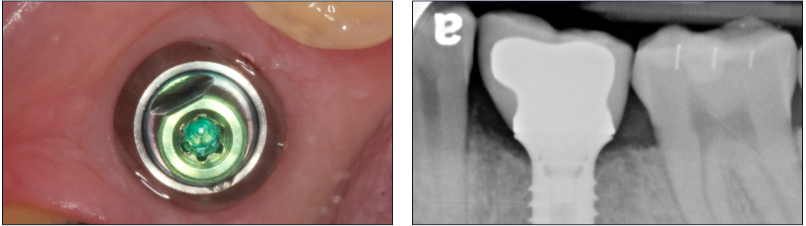

Initial implant design selection has a significant bearing on the final outcome and can eliminate many potential problems associated with cementation. For example, tissue level implants have a basic design that could be considered more advantageous for cemented restorations compared to the design of standard bone level implants (Figs.5,6).

Fig. 5 – Tissue level root form implant #19 illustrating a broad emergence profile design concept in the cervical area. This design creates a natural dam protecting the axial surfaces from cement extrusion.

Fig. 6 – Standard bone level root form implant illustrating a more common cervical implant design concept. Direct line access can channel cement apically with no impediments.

By having a more horizontal platform design, it can be said that a tissue level implant design is inherently better at preventing axial cement migration. Because tissue level implants create a gingival dam, these implants naturally prevent cement from migrating apically and bonding to the axial wall of the implant as opposed to the straight line access of a bone level design implant. Additionally, a tissue level implant with a wide gingival platform has been referred to as “the ultimate platform switch” design.

According to Tarnow, the concept of platform switch is to isolate the implant-abutment connection as far away from the crestal bone as possible.9 Tissue level implants have an inherent design that accomplishes this inadvertently by having the implant-abutment junction at least 1mm from the crestal bone margin (Figs. 7,8).

Fig. 7 – Tissue level root form implant #19 illustrating a broad emergence profile design concept in the cervical area. This design creates a natural dam protecting the axial surfaces from cement extrusion.

Fig. 8 – Standard bone level root form implant illustrating a more common cervical implant design concept. Direct line access can channel cement apically with no impediments.

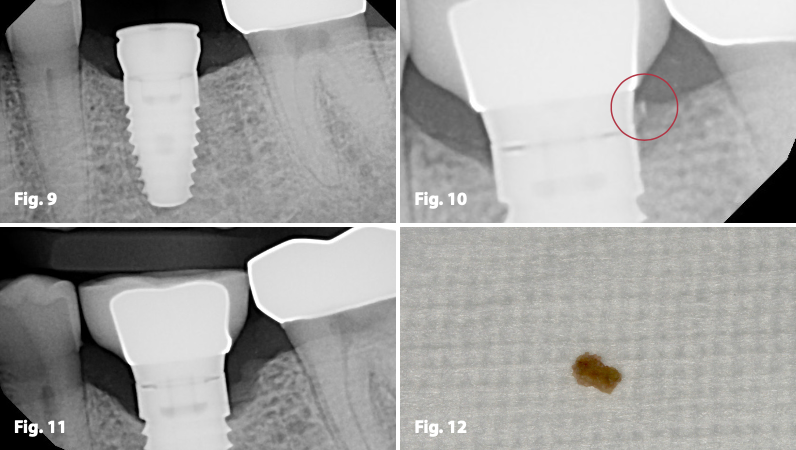

Historically, bone level implants have been a much more popular implant design selection over tissue level implants and the likely reason for this is that most general dentists completely defer the initial implant selection to the specialist. Conversely, the design of bone level implants creates a much more “direct route” for cement to be expressed apically, thus causing a potential irritant to the crestal bone, and much more importantly, crestal bone loss. If cement were to be left bonded to the axial surface of the implant body, the potential results can be catastrophic (Figs. 9,10,11,12).

Fig. 9 – Root for implant #19 with cement retained PFM crown. Initial implant placement illustrating excellent crest- al bone retention.

Figs. 10-12 – Post cementation radiographs showing retained cement on distal margin leading to crestal bone loss. Dislodged resin cement flash after removal 2 months post op.

Due to the possible catastrophic ramifications of cement extrusion, it is imperative that dentists take special care to insure that no cement is expressed apically when cementing crowns upon bone level implants.

Although bone level implants are obviously an excellent choice for many edentulous situations, special care must be taken when cementing crowns onto these implants. Again, bone level implants are place much more often than tissue level implants and unfortunately this straight-line dynamic can lead to many more cases of retained cement.

Additionally, many or most implant abutment systems offer a horizontal platform design for both stock and custom abutments that can be incorporated into the final restoration.

Many of these different abutment designs can be used with either bone level or tissue level implants. By considering and employing some of these initial implant design decisions, the restoring clinician is able to create better restorative situations that can aid in the prevention of apical cement migration and preservation of crestal bone.

2. Creating Problems, Preventing Problems

Another important aspect of fixed restorations is the selection of the final cement itself. It is crucial that the clinician consider all of the luting characteristics of a cement before employing it to secure a crown over an implant abutment. Ease of use, hydraulic pressures, final cleaning, and bond strengths are some of the most important issues to consider. The popularity of cosmetic dentistry over the past 20 years has dramatically increased the usage of resin cement overall and the ease of use adds to the overall convenience (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13 – Cosmetic CEREC restorations cement with resin cement. Note excellent marginal adaptation and seal.

Because of this popularity, resin cements are considered one of the best luting agents overall in general dentistry. Some of the reasons these cements are so popular are marginal seal, retention, strength, and esthetics. Unfortunately, these cementation principals that apply to cosmetic dentistry performed on natural teeth may not always apply to implants in the same manner. This widespread familiarity can lead to complacency and a lack of focus when choosing the best cement for implants.

Many of these cement selections are based on typical restorative situations where a ceramic restoration is being bonded to natural tooth structure, thus adding overall strength to the porcelain restoration itself. With the development of zirconia based restorations, the benefits of resin bonding are less critical, especially when cementing these restorations to metal abutments. Because the bond strength of resin cement to metal is not as important, the overall retention of restorations over implants relies more upon fit and Ferrule effect than the actual bond strength of the cement to material interfaces. Another consideration is that the marginal seal for decay prevention is also not as crucial compared to that of crowns on natural teeth. Because of this, the selection of a non-resin cement for cementation over implants could be a more advantageous selection compared to resin cement and its possible complications.

If a resin cement is chosen to secure crowns over implants, the practitioner must consider the potential problems associated with retained cement on the implant body itself and take special care to avoid extruding cement apically. As every dentist knows, resin cement that has bonded to the roughened axial surface of a dental implant is impossible to remove without surgical intervention and a high speed handpiece. Because of this potentially catastrophic situation, it is beneficial to consider alternative cements that are easier to clean and less likely to actually bond to the implant body surface, thus causing crestal bone loss.

3. Solutions and Preventions

When cementing an implant restoration, whether a single unit or multi-unit bridge, procedural setups and preparations are paramount to creating clean margins with no apical extrusions. Because implant supported crowns are structurally different than tooth borne restorations, it is important to focus on the cementation process itself and the issues that can be created. Unfortunately, many times clinicians must address significant problems that were created unnecessarily or previously overlooked. By having a complete cementation setup with instrumentation specifically designed for cement removal around implants, many of the issues related to cement migration onto implant surfaces can be completely eliminated.

PREVENTION IS PARAMOUNT.

Nowhere is this more true than when cementing crowns over implants. Preventing cement retention to the axial surfaces of implants initially is far and away the best course of action. If early crestal bone loss can be prevented from the beginning, an implant has a much better chance of long term success and complete bone retention.

CREATE GINGIVAL BARRIERS.

By gently packing a layer of retraction cord or Teflon tape, a gingival dam can be created that protects the sulcus from cement intrusion. This simple step adds an additional layer of protection and gives the clinician confidence that all external cement was removed during the final cleanup process.

THIN CEMENT LAYERS.

Fig. 14 – Tissue level implant with luted crown showing acceptable marginal adaptation and no excess retained cement that could cause crestal bone loss.

An accurate, well fitting final restoration does not need much cement at all to achieve good, long term retention when luted upon an implant abutment (Fig. 14).

In fact, “less is more” in most circumstances. By coating the inside of the restoration with the thinest film layer possible, the dentist can avoid expressing excess cement out from under the margins and possibly in an apical direction towards the axial wall of the implant itself.

CLEANING AIDS.

Instead of using just the standard cementation setup, consider adding additional instruments and disposable supplies to aid in cleaning cement from around implants. Micro brushes, scalers, woven floss (Superfloss-Oral B), and proxy brushes are just a few of the adjuncts that can help tremendously in cleaning final cement around an implant before the final cure.

SECOND OPINIONS.

Another set of eyes is always beneficial in spotting problems. By having the assistant look closely from their alternative field of view, they can often spot retained cement that would otherwise be missed by the doctor.

POST-OP XRAYS.

How many times has a clinician thought all excess cement has been removed only to find it later on X-ray at the next recall appointment? Even though a standard 2-D X-ray doesn’t show the buccal or lingual aspects, post-op X-rays are imperative to assure that all cement is removed from under the gingival margins.

POST OP APPOINTMENTS.

A good practice is to bring patients back at the 4-6 week mark for a quick check and Xray. If initial bone loss is noted, it is much better to find and treat this quickly to avoid further damage or even the complete loss of an implant. Most patients have no idea that bone loss is occurring and are often asymptomatic until there is significant inflammation or infection.

“An Ounce of Prevention is Worth a Pound of Cure”

4. Lessons Learned

It is well documented that cemented implant restorations can deliver wonderful long term solutions for missing teeth. The initial implant design selected can have a significant bearing on the final result and long term success rate of cemented restorations. Although these restorations can serve the patient well for many years, extra attention and care must be taken when cementing crowns with permanent cement.

Additionally, applying inappropriate cosmetic principles and a lack of attention when cementing the final restoration can lead to future problems. By concentrating on the initial planning phase and the final cementation, the treating dentist can minimize, and hopefully prevent, cement retention into implant surfaces. The benefits of this focused attention are the prevention of future crestal bone loss and ensuring a higher degree of long term success for cemented implant restorations.